Ten years ago, in May 2015, a fuel truck loaded with gasoline changed its route to avoid intense clashes raging around and within the Yemeni city of Taiz. At the time, the city was already under siege imposed by Houthi armed forces, designated as a terrorist group. Yemen’s economy was collapsing, living conditions were deteriorating into catastrophe, and the country was facing a crippling fuel crisis.

This gave the fuel truck entering Taiz enormous humanitarian, economic, and even military significance.

The truck narrowly escaped direct crossfire — but not the consequences of war. In the densely populated neighborhood where it broke down, the fuel it carried ignited, engulfing dozens of gathered civilians in flames. It was one of the most horrific civilian tragedies of the Yemeni conflict.

A New Market for War

The story of the “hell truck” is rooted in the start of the conflict, when the Houthis sought to consolidate control over the oil trade by issuing a decision known as the “liberalization of fuel imports.” This move reflected their understanding of the sector’s critical importance: oil accounted for roughly 75% of Yemen’s public budget revenues, according to statements by Minister of Oil Saeed Al-Shamasi, reported by the official Saba News Agency last year.

This close link between oil and the national economy motivated the Houthis’ attempts to seize production and export sites, especially the Safer oil facility in Marib — the largest in Yemen. Armed resistance, however, prevented them from taking it. They did, however, succeed in seizing Hodeidah governorate on the western coast, including its strategic port and oil terminals at Ras Issa and Al-Salif.

The Houthis subsequently restructured the oil market to serve their economic interests, manipulating import mechanisms, fostering a systemic environment of corruption, manipulating quantities to collect demurrage fees, imposing levies under the banner of the “war effort,” and adding five Yemeni rials to the price of every liter of fuel entering the country. They also encouraged smuggling and the growth of a vast black market.

Fuel — once a national resource meant to serve the population — was transformed into an instrument of internal siege, worsening humanitarian suffering. Yemen experienced repeated and severe fuel crises. In April 2015, hospitals in Aden and Taiz were forced to shut down due to diesel shortages. The situation in Taiz was particularly dire as the Houthi blockade tightened its grip on the city.

A Forced Path

In Taiz, fierce fighting broke out between Houthi fighters and resistance forces composed of armed civilians and the national army. Supported by military units loyal to former president Ali Abdullah Saleh, the Houthis controlled strategic hills in the city center — such as Al-Qahira Castle, the Political Security building, and the Al-Ikhwan complex — effectively controlling the city’s main southern streets with their firepower. Meanwhile, battles raged around Jabal Jarra and Jabal Wa’ash to the north, rendering the movement of trucks and vehicles towards the city’s northern and eastern sectors extremely dangerous.

The Houthis controlled major roads and supply routes, imposing measures that paralyzed civilian movement, restricted freedom of mobility, and obstructed the entry of goods, food, and medical aid.

In this complex environment, a fuel truck carrying approximately 45,000 liters of gasoline arrived in Taiz. Fearing Houthi snipers, the driver was forced to navigate through unconventional routes, according to a resident of the Al-Darbah neighborhood.

In Al-Darbah, the truck’s driveshaft broke down, forcing the driver to stop in the middle of a narrow road unsuitable for long vehicles. Vehicles belonging to resistance fighters and the army soon arrived, seeking fuel. After several barrels were filled, seven armed men from the neighborhood intervened and stopped the unloading, insisting that the fuel was intended for civilians. Local mediators — affiliated with the resistance — attempted to resolve the dispute.

According to one mediator, the armed group refused to allow further unloading. To avoid internal conflict, the resistance and army vehicles left the area.

A Tragedy Amid War

The fuel crisis in official markets was severe. As the war and siege intensified — particularly in Taiz — people’s living conditions deteriorated sharply. The conditions in May 2015 drove many Yemenis to turn to the black market, including ordinary civilians.

One survivor recalled:

“A 20-liter jerrycan of gasoline cost 50,000 Yemeni rials — around $200 at the time. People came with cooking pots to fill fuel from the truck’s tank. People were desperate.”

At midnight, gasoline began being siphoned into plastic containers using primitive methods and without any safety precautions. By morning, as video evidence shows, a large crowd had gathered — car owners, bus drivers, and motorcyclists — swarming the truck like ants, siphoning fuel directly from the tank openings.

In a split second, the area turned into an inferno, leaving dozens dead and injured. Videos show thick black smoke billowing into the sky as terrified civilians fled. Families frantically searched for loved ones. “Where is my son?” cried one woman.

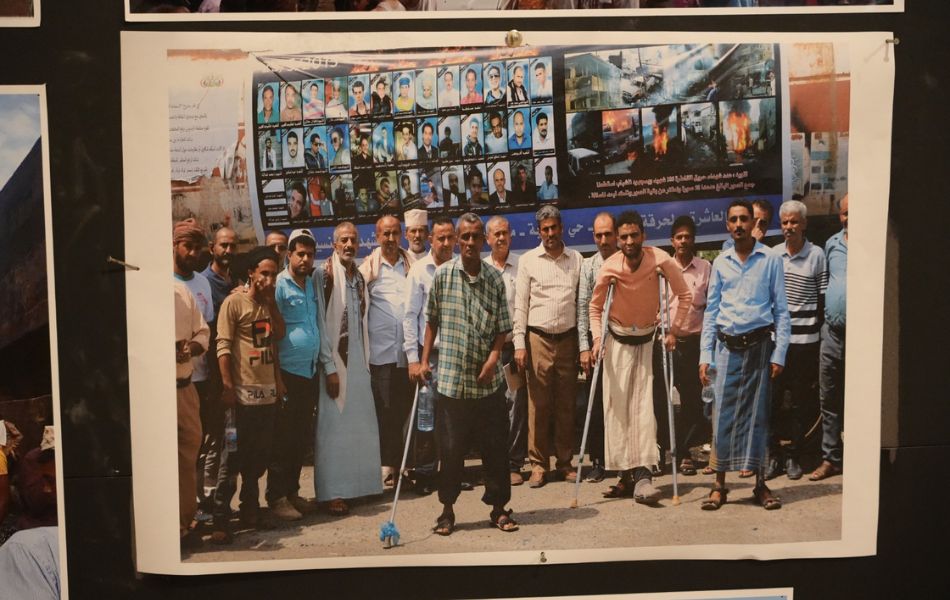

The inferno occurred in the early hours of May 25, 2015. No official figures exist on the total number of casualties and losses. SAM for Rights and Liberties documented 113 victims, including 42 fatalities.

Eyewitnesses described charred bodies piled together, human skin fused to metal, clothing melted away, and flames spreading to nearby buildings, motorcycles, and cars. Photographs reviewed by SAM show burned bodies lying in the street until late, with residents unable to identify them.

Loss Upon Loss

Al-Thawra Hospital, the largest public hospital in Taiz, was itself under siege in early 2015. Due to Houthi shelling, most doctors, specialists, and technicians had fled, leaving fewer than 40 staff — including doctors, nurses, pharmacists, lab technicians, cleaners, and support staff — according to Dr. Nashwan Al-Hassami, then head of the hospital’s emergency committee.

Most departments were closed, with all patients — internal medicine, surgical, burn, and inpatient cases — admitted to the burns unit, the only section shielded from sniper and artillery fire. The rest of the hospital was frequently shelled or struck by mortar rounds.

Dr. Al-Hassami said the first group of truck victims arrived with second- and third-degree burns, accompanied by a large number of relatives. More victims arrived in subsequent waves, eventually exceeding 120 patients. The hospital, however, suffered from severe shortages of staff, medical supplies, and solutions.

“We tried to mitigate the catastrophe by triaging the most critical cases and providing treatment with what limited resources we had,” Al-Hassami recalled.

The medical team began performing surgical procedures to clean wounds, remove necrotic tissue, and conduct operations under general anesthesia.

“We lost patients on the second day, more on the third, and more after a week. Every day, we lost someone,” Al-Hassami added.

The Immediate Perpetrator

According to three testimonies, the person directly responsible for igniting the fire was a young man named Hassouna. He demanded that the crowd make way for him to obtain gasoline, brandishing a lighter and threatening to set the truck ablaze. Suddenly, he lit the lighter and threw it onto the fuel-soaked ground, igniting the entire area instantly.

“M.S.,” who sustained third-degree burns and lost his brother, said:

“We never found my brother’s body. Seven charred bodies were buried together in one grave.”

Among the dead were six of the seven armed men who had insisted on taking control of the truck. Among the injured was Hassouna himself. SAM’s investigation indicates that Hassouna later fled Taiz’s government-controlled areas and now lives in Houthi-controlled territory, reportedly fearing retaliation from victims’ families and prosecution.

A Decade Without Justice

This year, residents of the neighborhood launched an initiative to repurpose the burned fuel truck as a water tank.

“But even so, our psychological wounds have not healed,” said one victim’s relative.

Another survivor, pointing to his leg, said:

“I scratched it a few days ago, and now it’s turned into a wound again.”

Despite the passage of ten years, no serious steps have been taken to address this tragedy. Victims have not received post-incident medical care. Many continue to suffer from physical and psychological trauma — and financial hardship.

“I sold everything I owned to buy ointments and medicine,” said one victim. “We haven’t received any support — not from the government, nor from international organizations.”

Another relative stated:

“We’re not asking for the impossible. We just want our loved ones to be recognized and listed as martyrs and wounded.”

In this context, SAM for Rights and Liberties calls for urgent action to compensate the victims and their families — at the very least by including them in the lists of fallen and wounded soldiers and granting them monthly stipends. SAM also urges the launch of an independent and transparent investigation to determine direct and indirect responsibilities for the tragedy, and to address the underlying causes — including lifting the siege on Taiz and regulating the fuel trade.